Last week, the Houston Chronicle editorial board published an opinion piece titled “Robbing HISD” and suggested that we as voters have the opportunity in November to reject a “broken and busted” school finance system. They urged us to vote “against” HISD’s upcoming ballot measure and explained that doing so would allow us to save the district and its students the indignity of handing over $162,000,000 to the state.

The Chronicle was wrong.

Unfortunately, our choice on November 8th isn’t whether to submit to a $162 million recapture payment. Rather, it’s how do we want to pay what we owe. The consequences of our choice will determine whether the district and our students lose another $30 million over and above the $162 million HISD already owes the state, a $162 million cost the district planned for with painful budget cuts this past spring, a $162 million payment which trustees unanimously budgeted for in June.

The choice on the ballot for us is do we pay recapture the easy way—$162 million through attendance credits—or do we pay recapture the hard way—$192 million through the loss of taxable property.

Furthermore, voters should know the facts behind recapture and why many HISD trustees and other city leaders might be advocating for us to vote against the measure in order for them to either not have to make tough choices or explain hard votes in the future or to help them gamble their way out of the poor choices that brought HISD to this point.

But this is way more complicated than the Chronicle and many trustees would have us believe, so let’s start at the beginning and talk about how we got here...

ATTENDANCE AND ENROLLMENT.

Many opposed to HISD paying recapture describe it in terms of need. The Chronicle stated the fact “that the district with the largest number of poor families will have to give away critically needed resources” was a sign of a broken system. The Chronicle also characterized the ballot language about “attendance credits” as “misleading” and“obtuse vernacular.” These statements make it sound like those who wrote this editorial never bothered to read Chapter 41 of the Texas Education Code, otherwise known as Robin Hood, before telling us how to fix it.

On the contrary, the degree of need students have in a district has nothing to do with recapture. Certainly student need significantly impacts the amount of state aid a district receives, but that calculation is completely separate from the Robin Hood process. So separate even, that you find it in a completely different law—Texas Education Code Chapter 42.

So what does impact the recapture calculation? Attendance and enrollment.

What was truly misleading was for the Chronicle to dismiss Houston ISD’s status as property wealthy while altogether ignoring the concept of attendance and enrollment. The Chronicle’s editorial didn’t once use the word enrollment as it criticized the law and asked us for our vote.

So let’s take a look at how it really works.

For each student who is present in class each day, the district effectively earns a little piece of funding for next year’s budget—essentially they earn attendance credits as students show up for school. The overall enrollment for a district or school is calculated as its “Average Daily Attendance,” and that is used to allocate state funds to districts.

In the state’s calculation of whether a school district is property wealthy or not, it uses the combination of the number of students enrolled in schools and the amount of taxable property the district has available to fund those schools. A district being subject to recapture is essentially a district that has reached a specific limit of taxable property per student enrolled.

So when the legislature was devising a system to exchange value between property wealthy districts and property poor districts, they created a currency based on student enrollment called “attendance credits” and provided a method by which districts with too much property wealth relative to their student population could essentially “buy” additional credits from the state thereby transferring money from that property rich district to the state which, in turn, would owe additional funds to a property poor district that doesn’t have enough tax revenue relative to its enrollment size.

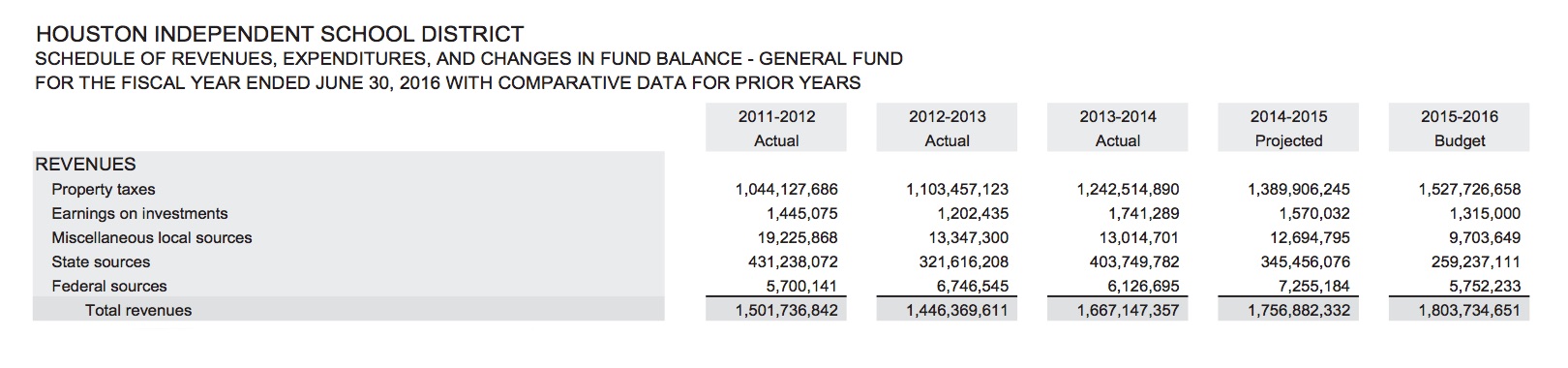

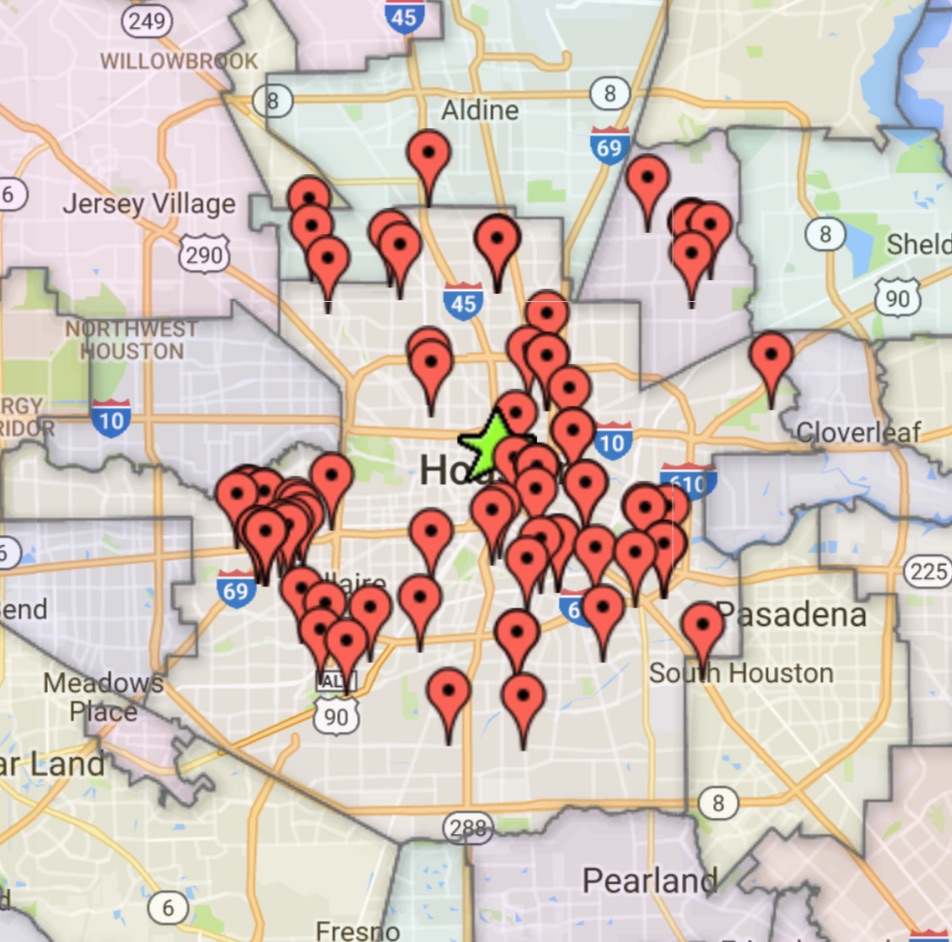

Looking at Houston ISD’s own financial statements and enrollment projections, we can see that property values and corresponding tax revenues have dramatically increased over the last five years, up 46%. Meanwhile, HISD’s student population hasn’t kept up, increasing at a mere 7.5% pace over the same period with enrollment predicted to remain flat through 2019.

It’s right here—this 46% percent increase in tax revenue versus a 7.5% increase in student enrollment is, in a nutshell, why Houston is in recapture.

Not because of outdated funding formulas. Not because of the state doesn’t think our students are needy enough. And certainly not because the voters choose to accept it.

Interestingly, a report from Houston ISD discussing the enrollment forecasting model used to predict future years specifically states that one of a number of factors limiting HISD’s growth is “increased competition from charter schools.”

This brings us to the next important part of the story.

FUNDING LOCAL STUDENTS.

Many HISD trustees who are asking you to vote against the proposition are fond of saying that our local tax dollars need to stay here in Houston to educate local Houston students. The Houston Chronicle’s editorial board said, “Houston's economy is strong and diverse, but to maintain that edge Houston needs well-educated students.” But by saying that in the context of advocating for HISD to keep all of its property tax is to suggest that HISD is the only place within its borders where public school students are educated.

This simply isn’t true.

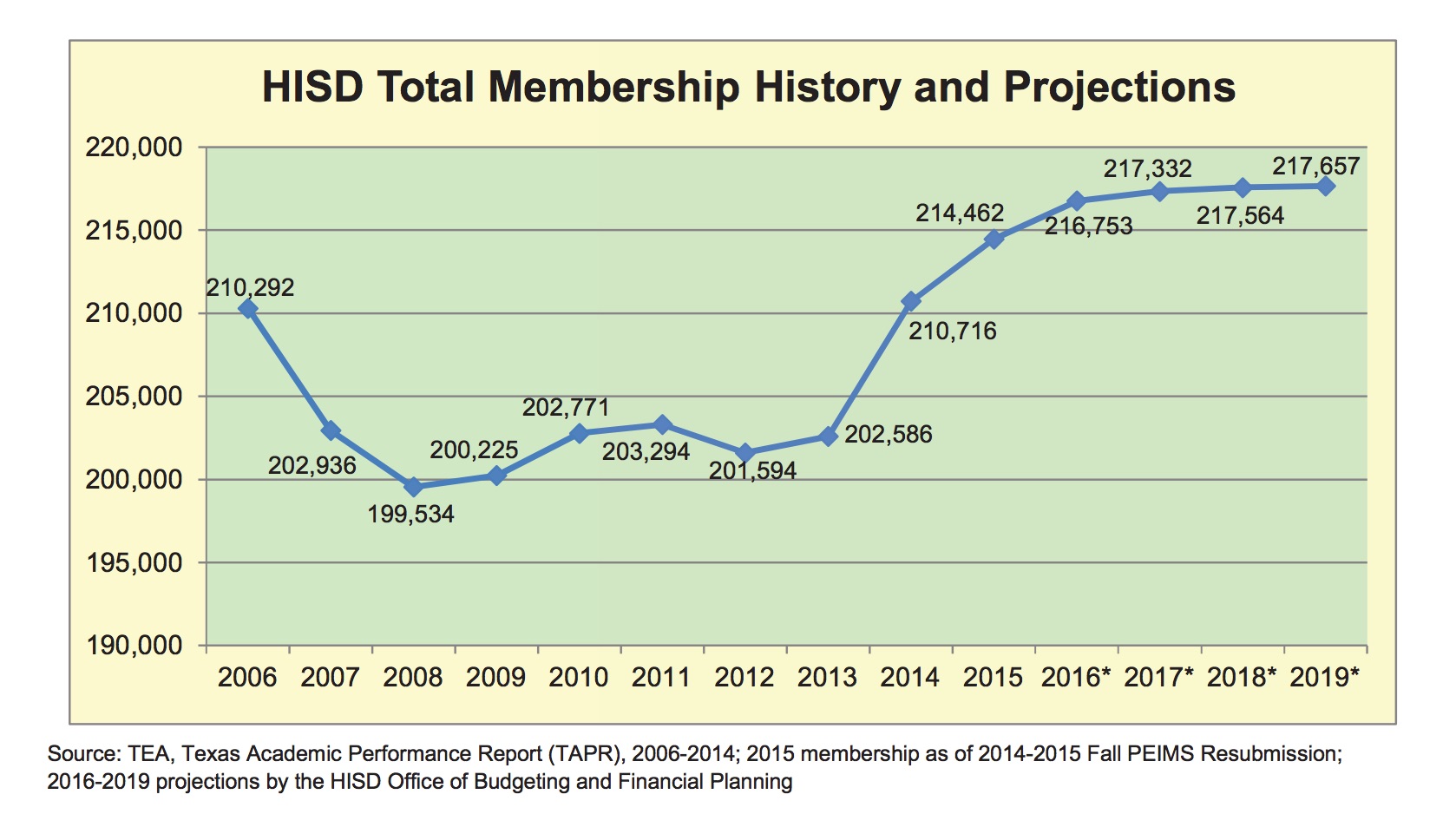

What they leave out of the argument is that 35,670 kids go to public charter schools inside HISD’s boundaries. The three largest providers: KIPP, Harmony and Yes Prep serve approximately 30,000 of them.

Here’s a map of all the public charter schools inside HISD’s boundaries.

Fun Fact:

If you took these 35,670 public charter school students and formed them into a new school district, it would be the size of Spring Branch ISD and be the 35th largest school district out of almost a thousand in the state. Think about that—an entire Spring Branch ISD of students going to school inside of HISD but not going to HISD schools.

Let’s do some math. (Stay with me.)

Take that public charter school enrollment just mentioned—35,670—and multiply it by HISD’s average annual spending per student—$8,620—and what do you get?

$307,475,400

This is a conservative estimate as smaller districts and charter schools pay substantially more per student per year, but even at that level this amounts to almost twice the $162 million HISD is being asked to pay in recapture.

Houston ISD’s board and administration have historically been pro-charter and have suggested that competition and choice in schools benefits Texas’ public school system. And in the competition of who can generate the most charter students, HISD is a big winner. These 35,000 charter school students represent 15% of Texas’ entire charter school enrollment. By comparison, HISD’s enrollment, as large as it is, only accounts for 5% of Texas’ non-charter students. That means HISD creates three times its fare share of public charter school students.

So who should we ask to pay for these Houston students?

Should Austin? Should Plano or Midland? What about Galveston or Spring Branch or one of the other quarter of Texas school districts already paying recapture?

It seems to me that if property taxes provide the majority of funding to public schools in this state, then property owners here in Houston ISD have a significant responsibility to these Houston public school students, as well.

THE EASY WAY OR THE HARD WAY.

HISD’s new superintendent Richard Carranza at many of his recent community meetings likes to characterize the referendum as a simple question. Right after telling attendees he has no official position, he restates the ballot measure with very different words and tells listeners to ask themselves this question to decide whether to vote for or against:

“Am I for sending our tax dollars to the state or am I against sending our tax dollars to the state?”

It’s as if Mr. Carranza lives in a world where local municipalities get to hold elections to determine whether they will comply with state law or not. You may agree or disagree with Robin Hood, but it is Texas law and our local election can’t change it.

Robin Hood has been the law since 1993 when the first school districts like Lake Travis ISD and Highland Park ISD started paying recapture to equalize student funding between districts with more property per student enrolled versus other districts. Twenty four years later, a great many districts have crossed that threshold of property wealth and begun paying recapture funding to the state. Virtually every one of those districts has done so by purchasing attendance credits.

Did those districts pay recapture with attendance credits because they all thought recapture was fair? No. They chose to do it the easy way having determined the higher cost of alternative options made them a bad choice.

Option 2 or "detachment" as it’s called has never been used. Some would have you believe this is because the state has never dared to take such an extreme measure and would be scared to do so, but really detachment has never been used because it has always been more expensive and no school district has been dumb enough to simply throw away money.

So why is "detachment" more expensive?

Well, if you're a property owner and you look at your tax bill, you'll see a single tax from Houston ISD. Last year, that rate was 1.1967 and this year it is set at 1.2067. But really, this rate is made up of two separate taxes. You can see them in HISD’s public notice prior to approving the budget this year.

The larger rate is called the Maintenance Tax which is the main tax used to pay for the annual operations of the district. The other is called the Debt Service Tax which is specifically levied to pay the bonds school districts issue for the construction and renovation of school properties. Recapture qualification is based on the operations tax, and should HISD have property detached to pay for recapture, an estimated $18 billion dollars of property would be taken to produce the operations tax equivalent of the $162 million owed.

But here’s the problem: Once the property is detached, HISD doesn’t have that property on its tax rolls to generate tax revenue for either operations or bond repayment. That bond tax, set at 0.18 cents per $100 of property value this year, multiplied by $18 billion in detached property comes out to approximately $30 million of lost bond taxes. So, in addition to losing the $162 million of operations revenue to recapture, the detachment options causes HISD to lose another $30 million of bond tax revenue.

It’s simple math, really, and Mr. Carranza should rephrase his question and tell you to ask yourself,

“Am I for sending $162 million of our taxes to the state or am I for allowing the state to take local property away which will cost us $192 million in forfeited taxes?”

On the November 8 ballot, if you vote “yes” or “for”, you’re voting for the easy way—$162 million.

If you vote “no” or “against,” you’re voting for the hard way—$192 million.

THE GAMBLE.

Of course most of the officials and leaders that are only telling voters half the story know most of this. Some don’t. Many do.

So why would they choose the hard way?

Well, Mayor Turner, the majority of the HISD school board and other leaders are trying to make a point. They believe that urban districts with lots of commercial property but many high poverty schools can only be responsible for looking out for themselves and actually need a lot more help from the state. Furthermore, they don’t see starving rural school districts with moderate student enrollment but dwindling property values as their problem to address. These cities are busy keeping taxes low to attract business and keep just enough tax revenue flowing to keep the lights on in public schools. They’ve been fighting this battle for some time and as the legislature has spent decades without action, these city leaders are getting desperate and ultimately choosing to roll the dice on the community’s ability to lobby the legislature to fix the problem before the “hard way” comes crashing down on the district and its tax payers.

But this gamble is fraught with problems. First and foremost, they’re gambling with taxpayer funds, teacher salaries and the quality of student education. The budget cuts already put in place this year to pay for the $162 million dollars owed were painful, and adding another $30 million on top of that would be a material hit to teachers and students.

Local education leaders say if the worst were to happen, the district could simply raise taxes a small amount to pay for the extra $30 million and that putting pressure on the legislature for a bigger change is worth risk. I guess they have a greater faith in the ability to raise taxes in this state. I think a lot of taxpayers, most of whom don’t have students in HISD, would have a different opinion, and under pressure from those taxpayers, one could imagine trustees not supporting such a tax increase—no matter how small—and choosing to simply cut more from HISD’s $2 billion budget.

Another reason this gamble is a bad bet is because of the legislature’s track record on school finance. Changing this system started almost as soon as it went into practice. Sixteen years ago, the politically connected Austin ISD thought it had the clout to change the system before it fell into recapture, but you know what happened? Nothing. They didn’t budge.

Even after a judge ruled the system unconstitutional a few years ago and the legislature was challenged to overhaul the system before it was potentially shut down by the courts, our representatives simply shrugged their collective shoulders and decided to wait and see what would happen on appeal. HISD itself has been lobbying and leading litigation to change the system for years, and they, too, have no results to show for it.

Now, after the Supreme Court has ruled that the flawed system is barely constitutional, its reasonable to assume that this legislature might be emboldened to keep it rather than feel forced to change. This history doesn’t mean HISD should stop advocating for a better system and or for more funding for its neediest students, but it is reason to might consider whether this poor track record supports adding $30 million to its wager.

IN CONCLUSION.

We must be really careful. Not only is the immediate cost of recapture to Houston on the line—the difference between $162 million and $192 million dollars this year, but so, too, is the battle to adequately fund public education in Texas.

If we let politicians oversimplify the problem to it being only about Houston keeping its money, we do Texas and its children a great disservice. If we advocate for keeping our taxes but ask someone else to come up with a solution for adequately funding the charter school students in our midst or the rural and suburban students far away, we dare the system to break down even further.

The real problems with school finance are imbedded in the disconnect between Chapter 41 (Robin Hood) and Chapter 42 (State Financing) or effectively the disconnect between how the state raises funds and how the state spends funds for public schools. If the Chronicle wrote anything accurately, it was in its description of the two bank accounts where funding in one offset spending from another. This is the real problem, but voting against attendance credits in November won’t fix that problem.

In a legislative year where there is already a great deal of focus on overhauling the school accountability system and top officials are advancing the reality of school vouchers which would divert public funds into private schools, I would be surprised if lobbying to save Houston ISD from recapture yields little more than a bandaid specific to Houston—and even that is improbable.

If that happens, local officials might claim victory. But I’d ask what will students everywhere else in Texas get? The answer is nothing. Those students would just be on the receiving end of yet another overall cut to public education in this state—a state already ranked in the bottom five states in K-12 public education spending—and collectively, we will have all missed out on an opportunity to talk about the real issues with school finance—how the state as a whole needs to increase its investment in equitable and effective public education for all.

So…

Step 1:

Vote in favor of attendance credits to minimize Houston ISD’s cost of paying recapture.

Houston ISD needs the money.

Step 2:

Advocate for meaningful public education finance reform in the upcoming legislative session.

Texas kids need to be a priority.